In the first 12 years of life, approximately 80% of all learning comes through the visual system.

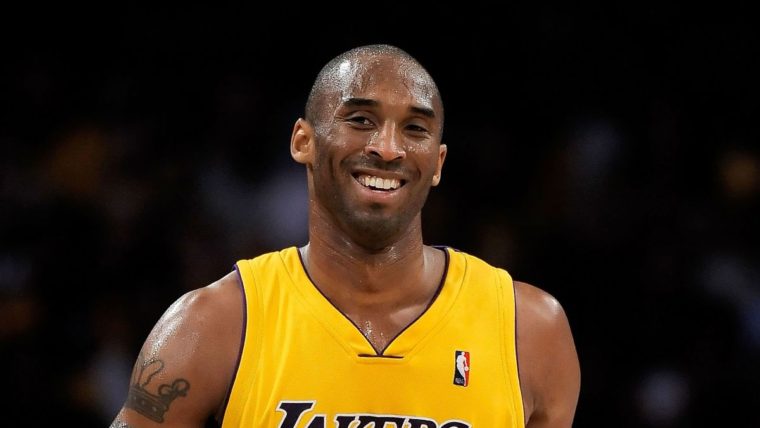

What it takes some people 80 years to accomplish, Kobe Bryant achieved in forty-one. He exemplified the power of intention and focused attention.

“I didn’t feel good about myself if I wasn’t doing everything I could to be the best version of myself.” ~ Koby Bryant

He started playing basketball at three years. When he was six, his father retired from the NBA and moved their family to Italy to be able to continue playing at a lower level. While there, Koby began to play basketball on a serious level and his grandfather kept him supplied with videos of NBA games for him to study.

At the age of 13, his parents returned to the United States for good. Koby recalls his days of being an insecure little boy, with no friends. On top of that, he said,

“I couldn’t spell, so the teacher told my mother that I was probably dyslexic, it was like somebody took me and dropped me in a bucket … in a tub of ice-cold water, because it shocked me.”

His mother made sure he got the help he needed.

It was then that he decided to channel his anger from the challenges and frustrations of dyslexia into sports and went on to become one of the NBA’s all-time exceptional players.

He made a deal with himself to stay focused on his goal and not be distracted by anything. He resolved to work hard every day, so that he could retire with no regrets, when that time came.

Kobe had an excellent work ethic and pushed himself to live the best way he knew how. Because he was super-focused on his craft, the world became his library. He looked at everything with this question in his mind, “How can this help me to become a better basketballer?”

He believed in playing with structure… with discipline. He believed in self-competition… always asking himself, “Is this the best I can do?”

Another concept he held was that you can learn more from your failures than your successes. He said that, “True strength comes from your vulnerability.”

He would review previous games with one of his coaches, then while playing, he was able to slow the game down in his mind and position players for optimal results. (a dyslexic strength) When a weakness emerges, the answer is there if you look at it.

With all his successes, he took time to be kind to those who would never be able to reciprocate. Did you know that he made over 200 Make A Wish kids’ dreams come true?

Here are 10 of his rules for success, gleaned from his various speeches:

He had an insatiable desire to learn more.

Listen to his final motivational speech here.

Which rule would you choose to motivate a struggling child in your life?

The one constant about dyslexia is its inconsistency. Each child’s encounter is unique. Even when two children have difficulty in the same area, reading for example, their struggle has different nuances.

Listen to dyslexic 2nd-grader, Maya, talk about her reading challenges.

Now, Jade gives a heartbreaking account of her 8th-grade dyslexic reading experience. Look through her eyes here.

Yesterday, you walked through one day at school with Henry.

Today, it’s your turn to experience what a dyslexic child sees when she reads. Here’s a fun way to understand and appreciate why learning and thinking differences can be so frustrating.

Go ahead and try a dyslexia reading simulation. Click the link below.

How did you feel while trying to complete the reading task in the allotted time?

Most dyslexic children do not want to get out of bed on a school day. The younger ones may still be tired after a long night completing home work. In addition to that, the older ones have social issues – being called dumb or lazy, being stared at or whispered about behind their backs.

Follow Henry through one day at school.

Has your child ever pretended to be sick to avoid going to school?

What did you do?

Today, I continue to put a megaphone to my voice to help children with dyslexia get the support they need to succeed – from parents, teachers, and everyone with whom they come into contact.

Most dyslexic people have strong visual/spatial abilities and weak auditory skills. How does that translate to real-life and living?

One important area that has significant consequence in childhood is following directions. This requires accessing of linguistic information presented in different forms.

Because this learning and thinking difference occurs on a spectrum, the level of difficulty following directions will vary from one dyslexic to another.

Some children have poor sight-word recognition but they are able to process language adequately. They understand phonics and apply it to reading, but have memory problems that translate to, among other things, following verbal or written directions.

Others have trouble processing language but are able to recognize sight words, so they rely on sight words when they see unknown words but are unable to sound them out. These children take mental pictures of word patterns and are able to read. These are the children who say “the” for any word that has that letter combination in it, like, their, there, them, they, etc.

Then there are those children with a mixture of the two. Their difficulty is a combination of the two experiences above.

In a very short video clip, Nessy illustrates how a child may appear to be lazy when, in fact, he has forgotten a direction given. Check it out here.

Instead of slapping labels on children who have difficulty following your directions, or punishing them for “deliberately” disregarding your instructions, seek ways of making the direction as easy as possible to visualize.

How have you felt when you could not remember all the instructions given to you or were distracted by something, then forgot directions you were following?

In 1967, Johnson and Myklebust stated that “a child who cannot read cannot write.” That makes sense, since some researchers, in their 2010 and 2011 studies, found that “reading and writing rely of related underlying processes.”

Just as they do with reading, most children with dyslexia have trouble with writing. This is demonstrated in a number of ways, for example, poor spelling, illegible penmanship, narrow vocabulary, weak idea development, and a lack of organization of thoughts.

You may hear a dyslexic child say, “I know what I want to say, but I just can’t write it down.”

Marianne Mullally, an Australian educator, explains it simply:

Just like their reading can be improved with time and various strategies, the writing of dyslexics can get better with explicit instructional strategies.

Keep in mind that reading must be worked on first. Michael Clark gives parents some tips and tricks to help their dyslexic children with their writing skills:

Now, here’s a fun activity. If you are non-dyslexic, do this exercise to experience what it is like for a dyslexic to take notes:

How did you do? Please share your thoughts with us.

Parents usually assume that their children are seeing normally. That’s not always the case.

According to the American Optometric Association, up to 80% of a child’s learning in school is through vision! This makes you child’s visual health extremely important.

Did you know that 1 in 10 children has a vision problem that’s significant enough to impact their learning? In the United States, that translates to over 5 million children.

Three vision skills necessary for optimal learning are:

Visual Acuity

When you take your child to the pediatrician, he gets a typical vision screening. Have you ever wondered if those screenings are foolproof? The National Center for Biotechnology Information says that at least 50% of vision problems are missed by typical screenings.

In addition to that, being assured that your child has 20/20 vision only tells you he can see at a distance. It does not dismiss the possibility of visual focusing, coordinating or tracking problems – all related to learning.

Convergence

Both eyes must work together, effortlessly and without hurting. That’s convergence. When they don’t quite work together, most likely, the child will sees words on a page bounce around. The child may then tell you that the words are blurry or swimming.

Most children under seven years will assume that everyone sees like they do and say nothing.

When this eye-jumping happens in a classroom, the child may complain of feeling tired, headaches (across the forehead, above the eye brows), and/or aching eyes. Some children tilt over to one side to read, thus creating a way to read with only one eye. For these children, reading is linked with distress and comprehension of what is read is low.

Convergence problems can also cause writing problems, because of poor hand-eye coordination.

Visuospatial Attention

Skilled readers are able to focus on individual words within a cluttered page of text, and after a word has been identified, they must rapidly shift their gaze to fixate on the next word in the line. These changes in visuospatial attention must occur rapidly and accurately to enable fluent reading of a page of text.

When the eyes do not move smoothly along together, the child skips words and phrases, or entire lines while reading.

A 2007 study showed that dyslexics have visuospatial attention deficits that parallel their deficits in some linguistic measures, like verbal short-term memory.

Does your child

It may be dyslexia, or it may be learning-related vision problems.

Be observant!

If you suspect your child is having vision problems, contact the College of Optometrists in Vision Development to locate a developmental optometrist in your area.

Have you ever had to take your child for vision testing because of learning difficulties?

A child’s high school experience can be pivotal. For a dyslexic, it’s an even greater achievement, considering that 35% of dyslexics drop out of high school.

My dearest K,

I can’t believe this time has come. You never thought you would achieve this much. But our God has been faithful! You are at the end of High School, and it’s your graduation day. Well done, my child!

Some Things Remain

Testing seemed to have been the first order of high school. Those pre- and post- IOWA tests seemed to be written in a different language and the New York State Regents examinations loomed ahead and you didn’t know what to expect. Now, the bulk of schoolwork had to be done at home, since school hours were spent in discussions and experiments.

You still struggled for hours, every night, to complete your homework assignments; and your late nights made it difficult to wake up early for school, the next day. But you pushed on. It was a blessing you had the Learning Ally audio textbooks to accompany your print books.

You still weren’t very motivated to go to school, but you went, without complaining.

Do you remember how, in addition to your school, you had to work through those brain exercises and the Learning Ears program? It seemed like intervention programs would never end, but I kept pushing and encouraging you.

A New Experience

High school was different from elementary and middle school. For you, it was a good change. Here students were expected to be responsible and you were no longer dependent on teachers.

The many intervention programs began to pay off. You’re reading better and not afraid to be called to read in class. You learned tips and tricks of blending with the crowd and appearing “normal,”

You were involved in more student interaction and collaborations and were accepted into the groups without question.

Teachers

Your teachers here were empowering and less punitive.

Your 9th grade homeroom teacher set the tone and spiritual foundation for your high school experience. She was kind, supportive, friendly, yet demonstrated excellent classroom control.

Your 12th grade homeroom teacher and Digital Media teacher (whom we found out later is also dyslexic) were great cheerleaders.

You history teacher taught you much about the philosophy of living, and kept you curious about life and the world.

I don’t know what you told him, since you determined not to let anyone in your school know you were dyslexic, but it was admirable of your Bible teacher to allow you to take his scripture memorization tests verbally, rather than written.

Your science teacher, Ms. A., took the crown. She was focused on your success. She was the reason you scored so high on the Biology Regents. She taught you how to explain yourself verbally and on a written test. She moved around the class and met you and your classmates on your level. The atmosphere she created in her classroom made it easy to ask any question, and not feel ridiculed. Along with that, she seemed to put extra effort into getting you to the point of clarity, then remembered to celebrate your successes and cheer you on to the next level. All in all, she made learning fun, and your high school experience enjoyable.

Your teachers didn’t seem bent on embarrassing you, but allowed you to take responsibility for your decisions and actions.

Friends

It was easier to relate to your classmates and you acquired female friends. Even when you misspelled or verbally mixed up words and phrases, your friends just laughed, corrected you and moved on. When you didn’t understand some concepts, they chuckled and explained it. It just wasn’t a big deal!

What relief I felt that you maintained a pleasant demeanor and displayed no more evidence of daily anxiety. The communal atmosphere certainly added to what I was doing to build your self-esteem. You took your inclusion in activities and the respect shown to you as evidence of your friends’ trust.

To top it off, your peers considered you to be smart.

Successes

Your work ethic began to pay off – you are reading better.

More importantly, you now understand the implications of your different thinking style and have discovered how to teach yourself to learn, and developed a personal manifesto:

Finally getting a grasp of how you learned helped you prepare for and pass you exams.

Your high school experiences helped you see that, although you may learn and see the world differently from others, the foundation for success is the same.

You made a conscious decision to pass and be a success in life.

Do you remember the knot-board you created for your club assignment? It was so creatively organized – so exceptional – the club director kept it as a sample to show future members.

Your decision to be intentional about your success permeated every area of your life.

You are admired by young people and adults alike.

Today, you graduate Valedictorian of your class. Yes! VALEDICTORIAN!!!

You deserve every moment of your celebration!

Look out College. Here she comes!

Love,

Mom

How has your child overcome personal challenges to achieve success in some area of life?

Only a few people have won an Emmy, a Grammy, an Oscar, and a Tony Award (EGOT). Caryn Elaine Johnson is one of them.

She was born on November 13, 1955 in Chelsea, New York and grew up in a housing project with her brother and mother, who was a nurse and later became a Head Start teacher.

In school, she was called “slow,” “dumb,” “lazy,” or “retarded.” She wasn’t diagnosed with dyslexia until she was an adult, so when school kept getting harder and harder, she eventually dropped out at 17. With her self-esteem low, she traveled a turbulent road in life, which included poverty, drug addiction, single motherhood, welfare, and a series of wide ranging jobs.

In his interview for the Child Mind Institute, the founder, Dr. Harold Koplewicz, called her a woman of grit and resilience.

Today, we know her as Whoopi Goldberg, actress, comedian, radio host, television personality, author and UNICEF International Goodwill Ambassador. Listen to her recall some of her challenges and her mom’s support in her interview with Quinn Bradlee:

She counsels parents to be supportive of their dyslexic children – “Stop trying to find a reason why it happened… It’s not your fault… Pay attention to how your child is doing stuff.”

Then, listen to her speak at the Goodwin College 2018 Commencement where she counsels the graduates, after receiving an honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters.

How can you build your child’s self-esteem at home to combat the negative labels in school?

When you consider the vast advancements that have been made in science and technology, and the multiple methods for accessing information, it is fair to say that schools and institutes of learning insist on using, as Dean Bragonier puts it, “the most archaic form of educational media.”

If dyslexia is considered a different way of thinking rather than a disadvantage; if the different patterns of strengths and challenges are kept in mind; if as much importance is placed on those strengths as their difficulties; then early intervention and continued support would be made a priority.

Imagine a world where the thinking skills that dyslexics excel at are used to prepare them to contribute to their communities and the world. What would be the possibilities?

You may be wondering what those skills are. Here are they:

After many years of struggle, usually, with very little significant support, many dyslexics gravitate to career paths that cater to their preferred way of thinking.

In my previous article, I cited some data from Dr. Gershen Kaufman. Here’s some more:

In his autobiography, Nicholas Negroponte, founder of the MIT Media Lab and the One Laptop per Child Association, called dyslexia the MIT disease because of how common it is among students on the campus of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

If you’re not already familiar with the world of dyslexia, it’s time to educate yourself about it and encourage every teacher and educator to do the same. After all, if one in five children are dyslexic, there is at least one child in every class who can be identified with dyslexia.

What are you willing to do to support the movement to reshape the teaching industry in the area of dyslexia?